SIV and HIV

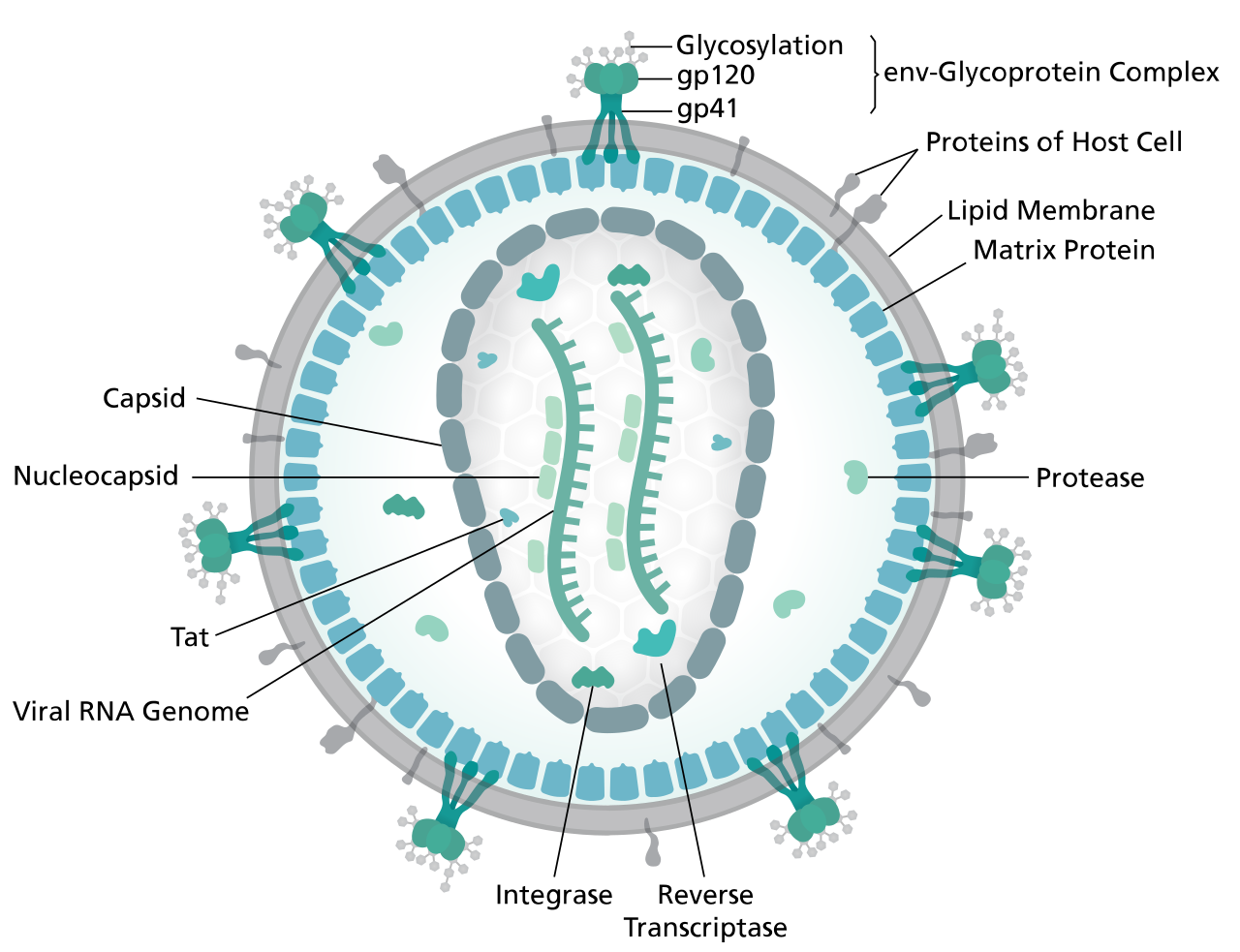

The Retroviridae viral family is well-known due to the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), etiological agent of the pandemic Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) [1]. In particular, five serogroups are recognized in the Lentivirus genus and cause persistent chronic infections in their associated vertebrate hosts, like primates, sheep and goats, horses, cats, and cattle [2]. HIV is most closely related to the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), arising from cross-species transmission of SIV from African nonhuman primates (NHPs) to humans [3,4,5,6,7]. The viral particle has an enveloped spherical structure with a diameter between 100 and 180 nm [8]. The envelope is composed of a lipid bilayer, which contains several surface proteins, some of which are produced by the virus, such as gp120 and gp41, and others of host origin [9,10]. They are complex viruses with two copies of a ssRNA(+) genome of 9,75 Kb with a 5’-cap and a 3’-poly-A tail [11]. The viral genome contains nine genes that encode 15 different proteins, plus two long terminal repeats (LTR) flanking it. Through the action of the reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme, the virus transforms its genetic material into DNA and stably integrates it into the host genome [12].

The gastrointestinal tract-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is the major target for the virus in the acute phase of infection, where there is massive viral replication and a significant decrease in active CD4+ T cells [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. These cells are destroyed by cytopathic effects or indirect mechanisms of apoptosis and the impact of these events on the GALT and adjacent lymphoid tissues are determinant in the progression of the disease. Indeed, infected cells can be destroyed through massive viral replication or enter a latent infection stage, where resting cells become permanent viral reservoirs [18, 19, 20].

In the initial phase, a viremia peak (presence of viral RNA in plasma) occurs in the pre-seroconversion phase, which is partially controlled by the host through the humoral and cellular immune response, reducing viral replication [17, 21]. The post-viremic peak period is called viral adjustment, where viral replication levels and CD4+ T cell rates enter into a dynamic balance with the destruction of virus and infected cells and the repopulation of CD4+ T cells by the host [15]. Furthermore, many factors are associated with innate and antiviral immunity to influence replication and establish infection control in the acute phase [22]. Therefore, the immune response exerted by cytotoxic activity, mainly by CD8+ T cells, is crucial at this stage of the infection, even before the formation of the adaptive response with viral neutralizing antibodies [23, 24].

The asymptomatic clinical period after acute infection is related to the antiviral action exerted by both the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses [16]. At this time of infection, T lymphocytes and NK cells have specific antibodies capable of binding to viral antigens on the surface of infected cells and eliminating them, through a cascade of antigen-specific cytotoxic mechanisms. However, the virus continues to replicate in the reservoirs, which induces a chronic systemic inflammation phase [20, 25]. The key factors in this system’s inability to eradicate the infection are the presence of inactive infected cells acting as a reservoir and the high rates of viral replication and mutation, which allow the virus to quickly adapt to the hostile environment created by the immune system. However, some patients are able to sustain this balance indefinitely, and they may have long periods with an undetectable viral load [26]. These patients are called non-progressors, intensively studied in search of mechanisms that induce this state of viral suppression in a different way [27, 28]. Host restriction factors are targets of study, in addition to infection controllers and non-pathogenic animal models.

In pathogenic infections, immune activation provides the proper environment for maintaining high rates of viral replication in active CD4+ T cells with high expression of the CCR5 co-receptor [29]. This protection scheme ends up exposing the organism to the virus and favors infection, which leads to a rapid decrease in CD4+ cells in the GALT even in the first weeks in both human and rhesus models [30]. Associated with other factors, there is a weakening of the intestinal barrier, enabling bacterial translocation from the lumen to the bloodstream. The cycle closes due to the strong induction of chronic immune activation and inflammation in response to the aforementioned events, which result in the activation of more CD4+ target cells. The progressive loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes culminates in immune failure leading to the AIDS stage, with the establishment of various opportunistic pathogens such as bacteria, viruses and fungi.

In non-pathogenic infection models, there is a natural reduction in CCR5 expression and a strong control of immune activation, which leads to the maintenance of CD4+ cell levels in both blood and gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), and consequently in the maintenance of the intestinal barrier, avoiding bacterial translocation [31 , 32, 33 ]. Therefore, there is no expressive depletion of CD4+ cells and, consequently, there is no disease progression [34, 35, 36].

NHPs are used as models for the study of human infections because they share physiological and anatomical similarities [37, 38]. The NHPs most used in research for vaccine development and evaluation of viral pathogenesis belong to the species such as African green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus; SIVagm) sooty mangabeys (Cercocebus atys; SIVsmm) and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta; SIVmac) for the study of HIV-1 [39]. As in humans, macaques are also susceptible to inefficient control of viral replication, accelerated apoptosis and generalized activation of T lymphocytes. Inflammation in these models shows that there is a strong induction of cytokine recruitment and expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines, such as type I interferons (IFN), restriction factors and the expression of several IFN-stimulated genes (ISG) commonly associated with the inflammatory state [40]. This shows that early stage immune activation levels are an indicator of pathogenesis [22, 41]. Furthermore, several markers of cell activation and proliferation have increased expression and there is a strong depletion of CD8+ T cells, showing the difference in the innate and adaptive immune response throughout the infection. On the other hand, African green monkeys and sooty mangabeys are similar with human non-progressors and develops a non-pathogenic relationship where there is viral replication, but this does not trigger chronic immune activation.

To date, the pathways used by non-pathogenic models to suppress the immune response are well documented [31,42,43]. This occurs due to the differential expression of defensins, which have antimicrobial activity, the increased expression of immunosuppressive cytokines (IL10, TGFβ and Tregs) and the upregulation of ISGs. These differential gene expressions happen precisely in the period after infection and in the transition from the acute to the chronic phase. In pathogenic infection, high levels of gene expression are directed towards the production of genes that act in the cell cycle, markers of activation and inflammation (i.e. MKi67+), apoptotic genes (i.e. TRAIL) and chemokines involved in T cell transport into the GALT, in addition to the chronic expression of ISGs [31].

However, much still needs to be clarified, as it is not known what triggers the cascade of events that leads to each of the infection models. The mechanisms that lead to this protection against progression are still unclear, and it is known that generalized immune activation even in the acute phase is directly linked to the pathogenesis of disease progression, correlating inflammation as a reflection of the presence of the virus in the ganglia [44]. In animals used as models for non-pathogenic infection, the virus is not transported to the nodes, which are not infected. However, what blocks the virus from proliferating in this compartment of natural hosts has not yet been identified. Furthermore, restriction factors are key parts in the natural blocking of zoonotic transmissions that require the adaptation of viruses during the passage from one species to another [45]. The study of these molecules can shed light on the evolution of the functioning and defense mechanism for blocking virus proliferation in different animals.

References

- Coffin J, Blomberg J, Fan H, Gifford R, Hatziioannou T, Lindemann D, et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Retroviridae 2021. J Gen Virol. 2021;102. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001712

- Gifford RJ. Viral evolution in deep time: lentiviruses and mammals. Trends Genet. 2012;28: 89–100. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.11.003

- D’arc M, Ayouba A, Esteban A, Learn GH, Boué V, Liegeois F, et al. Origin of the HIV-1 group O epidemic in western lowland gorillas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112: E1343–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502022112

- Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, Chen Y, Rodenburg CM, Michael SF, et al. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397: 436–441. doi:10.1038/17130

- Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Bailes E, Takehisa J, Santiago ML, et al. Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006;313: 523–526. doi:10.1126/science.1126531

- Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Neel C, Bailes E, Keele BF, Liu W, et al. Human immunodeficiency viruses: SIV infection in wild gorillas. Nature. 2006;444: 164. doi:10.1038/444164a

- Plantier J-C, Leoz M, Dickerson JE, De Oliveira F, Cordonnier F, Lemée V, et al. A new human immunodeficiency virus derived from gorillas. Nat Med. 2009;15: 871–872. doi:10.1038/nm.2016

- Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE. The Interactions of Retroviruses and their Hosts. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. Available

- Gelderblom HR. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. AIDS. 1991;5: 617–637. Available

- Goto T, Ashina T, Fujiyoshi Y, Kume N, Yamagishi H, Nakai M. Projection structures of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) observed with high resolution electron cryo-microscopy. J Electron Microsc . 1994;43: 16–19. Available

- Wain-Hobson S, Sonigo P, Danos O, Cole S, Alizon M. Nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, LAV. Cell. 1985;40: 9–17. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90303-4

- Goto T, Nakai M, Ikuta K. The life-cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Micron. 1998;29: 123–138. doi:10.1016/s0968-4328(98)00002-x

- Robertson P, Dwyer D. Laboratory Diagnosis of HIV Infection. 1993. Available

- Buttò S, Suligoi B, Fanales-Belasio E, Raimondo M. Laboratory diagnostics for HIV infection. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2010;46: 24–33. doi:10.4415/ANN_10_01_04

- Ho DD, Neumann AU, Perelson AS, Chen W, Leonard JM, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373: 123–126. doi:10.1038/373123a0

- Ho DD. Perspectives series: host/pathogen interactions. Dynamics of HIV-1 replication in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;99: 2565–2567. doi:10.1172/JCI119443

- Little SJ, McLean AR, Spina CA, Richman DD, Havlir DV. Viral dynamics of acute HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 1999;190: 841–850. doi:10.1084/jem.190.6.841

- Schrager LK, D’Souza MP. Cellular and anatomical reservoirs of HIV-1 in patients receiving potent antiretroviral combination therapy. JAMA. 1998;280: 67–71. doi:10.1001/jama.280.1.67

- Pankau MD. Dynamics of the HIV-1 Latent Reservoir. 2019. Available

- Alexaki A, Liu Y, Wigdahl B. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 and their role in viral persistence. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6: 388–400. doi:10.2174/157016208785861195

- Bangham CRM. CTL quality and the control of human retroviral infections. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39: 1700–1712. doi:10.1002/eji.200939451

- Bosinger SE, Li Q, Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Duan L, Xu L, et al. Global genomic analysis reveals rapid control of a robust innate response in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. J Clin Invest. 2009;119: 3556–3572. doi:10.1172/JCI40115

- Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68: 6103–6110. doi:10.1128/JVI.68.9.6103-6110.1994

- Lichterfeld M, Kaufmann DE, Yu XG, Mui SK, Addo MM, Johnston MN, et al. Loss of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation after acute HIV-1 infection and restoration by vaccine-induced HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200: 701–712. doi:10.1084/jem.20041270

- Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D, Shen X, DiGiuseppe JA, Taylor H, et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387: 183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0

- Saksena NK, Rodes B, Wang B, Soriano V. Elite HIV controllers: myth or reality? AIDS Rev. 2007;9: 195–207. Available

- Wang B. Viral factors in non-progression. Front Immunol. 2013;4: 355. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00355

- Poropatich K, Sullivan DJ Jr. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long-term non-progressors: the viral, genetic and immunological basis for disease non-progression. J Gen Virol. 2011;92: 247–268. doi:10.1099/vir.0.027102-0

- Coakley E, Petropoulos CJ, Whitcomb JM. Assessing chemokine co-receptor usage in HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18: 9–15. doi:10.1097/00001432-200502000-00003

- Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, et al. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200: 761–770. doi:10.1084/jem.20041196

- Manches O, Bhardwaj N. Resolution of immune activation defines nonpathogenic SIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2009;119: 3512–3515. doi:10.1172/JCI41509

- Veazey RS, Tham IC, Mansfield KG, DeMaria M, Forand AE, Shvetz DE, et al. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4(+) T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74: 57–64. doi:10.1128/jvi.74.1.57-64.2000

- Veazey RS, Mansfield KG, Tham IC, Carville AC, Shvetz DE, Forand AE, et al. Dynamics of CCR5 expression by CD4(+) T cells in lymphoid tissues during simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2000;74: 11001–11007. doi:10.1128/jvi.74.23.11001-11007.2000

- Pandrea I, Sodora DL, Silvestri G, Apetrei C. Into the wild: simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in natural hosts. Trends Immunol. 2008;29: 419–428. doi:10.1016/j.it.2008.05.004

- Ansari AA, Silvestri G. Natural Hosts of SIV: Implication in AIDS. Newnes; 2014. Available

- Silvestri G. Naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys: are we closer to understanding why they do not develop AIDS? J Med Primatol. 2005;34: 243–252. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00122.x

- Nath BM, Schumann KE, Boyer JD. The chimpanzee and other non-human-primate models in HIV-1 vaccine research. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8: 426–431. doi:10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01816-3

- Paiardini M, Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Silvestri G. Lessons learned from the natural hosts of HIV-related viruses. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60: 485–495. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123753

- Spertzel RO. Animal models of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Public Health Service Animal Models Committee. Antiviral Res. 1989;12: 223–230. doi:10.1016/0166-3542(89)90050-8

- Jacquelin B, Mayau V, Targat B, Liovat A-S, Kunkel D, Petitjean G, et al. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of African green monkeys induces a strong but rapidly controlled type I IFN response. J Clin Invest. 2009;119: 3544–3555. doi:10.1172/JCI40093

- Williams KC, Burdo TH. HIV and SIV infection: the role of cellular restriction and immune responses in viral replication and pathogenesis. APMIS. 2009;117: 400–412. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02450.x

- Lederer S, Favre D, Walters K-A, Proll S, Kanwar B, Kasakow Z, et al. Transcriptional profiling in pathogenic and non-pathogenic SIV infections reveals significant distinctions in kinetics and tissue compartmentalization. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5: e1000296. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000296

- Kornfeld C, Ploquin MJ-Y, Pandrea I, Faye A, Onanga R, Apetrei C, et al. Antiinflammatory profiles during primary SIV infection in African green monkeys are associated with protection against AIDS. J Clin Invest. 2005;115: 1082–1091. doi:10.1172/JCI23006

- Silvestri G. Immunity in natural SIV infections. J Intern Med. 2009;265: 97–109. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02049.x

- Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1: a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.